“Britain as we have known it for the last two hundred years - as Global Superpower, the Empire on which the Sun Never Set, was born in this very building, on that night of heroic triumph in 1815, as Major Henry Percy handed the Prince Regent the despach confirming Wellington’s win at Waterloo in the room right above our heads. And this Britain, ever high upon the opiate of imperial triumph, remains enshrined throughout its halls, its dining rooms and bars. But soon enough, for better or for worse, this Britain we have known since Victory at Waterloo was declared beneath this roof is about to die - and it is to do so because we have, as a nation, yet to recover from that jingoistic high so finely represented by this institution and everything within it...”

In July 1815, in an event widely accepted to have ushered in a century of undisputed British dominance over global geopolitical and military affairs, Major Henry Percy delivered the Waterloo Dispatch, telling of Wellington’s forces’ victory over Napoleon, to Number 16, St James’s Square, where the Prince Regent was attending a high-society party. Almost exactly 200 years later, the UK would vote to leave the European Union, in a move widely believed to be representative of Britain’s national insecurity and inability to find geopolitical purpose following the loss of Empire and its economic decline relative to other great powers, orchestrated by a contingent of politicians and lobbyists who had similarly made No. 16, St James’s Square - today, home of the East India Club, a gentlemen’s club dedicated to celebrating and “evoking the days of Empire” (to quote its own website) - a regular haunt. In March 2019, exactly a week before negotiations between the UK and EU were originally due to finish and their separation completed, I led a group of artists, activists and students into the Club to host a live “intervention,” analysing the last 200 years of British social and geo-political history, the legacy and destructive history of the British Empire, and the continued racism, sexism, classism and imperial nostalgia underpinning so much of high-class, conservative Britain - in the run-up, falsely posing as a young right-wing historian looking to host an “artifact party” in the style of Hans Sloane, founder of the British Museum, in one of its private meeting rooms in order to gain authorisation from the Club’s leadership for what was to be a damning indictment of the Club and its politics.

Taking on the collective name ‘The Joan Carpenter Club,’ a fantasy collective of feminist infiltrators and avengers I was developing for my Degree Show at the time (see here), over four hours on the night of the 22nd March we undertook a number of creative activities within the East India Club’s walls - commencing with a brief tour of the building, conducted undercover in our dress-code-abiding “smart” clothes, in which I introduced the history of No. 16 and the connections to imperial history and “old-boy” political culture laced throughout its walls. Once in our private meeting room, stripped out of our formal-wear and into more comfortable (and in my case, as a trans woman having to hide her identity, women’s) clothing, we engaged in a series of talks, comedic sketches, collective role-playing exercises and caricaturing/satire-writing activities intended to explore the histories of British India so roundly sanitised and ‘Disneyfied’ by the portraiture and artefacts littering its walls; poke fun at the figures sustaining atmospheres of hostility and discrimination towards migrants, refugees, former colonies and their citizens, as well as other marginalised minorities, within post-Brexit Britain; and the inequalities inherent in the nation’s continuing class-based socio-economic hierarchies.

The intervention began with a speech, considering the two hundred years between the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the Brexit referendum, and shredding apart numerous historical and political narratives derived from the era of nineteenth and early twentieth-century British geopolitical dominance - or worse, hopelessly false interpretations of the era - as they have been deployed by major figures from the EU Referendum’s Leave campaign, and the contemporary Conservative Party in general. Following this came a sketch - ‘Purse’s Creche’ - in which my dear friend and fellow performance artist Lucia Coppola reimagined a prominent character from her own practice, Purse the Nurse, as the careless and grouchy owner of a daycare centre, charged with caring for a number of inanimate babies - ranging from a handbag, to a pair of Doc Martens, to an antique fire extinguisher - in a creche we had constructed in one corner of the room. The inspiration for this one particular sketch came from an exchange had during the East India Club’s 2018 AGM, in which the question of permitting women members was raised and promptly, swiftly shot down, with the use of the particularly offensive point that if we were to allow women to join, we’d have to build a creche somewhere as they’d have to bring their babies along with them, as though all women were baby-making stay-at-home mums who couldn’t maintain a career, afford professional childcare or babysitters, or - God forbid - make them share some of their domestic duties.

This short sketch was promptly followed by a role-playing exercise, named The Rotten Raj, in which I asked my guests to assume the roles of various figures associated with eighteenth and nineteenth-century British India, dressing themselves in costumes made using scrap fabric and fancy dress clothing procured from charity shops, and acting out - as best they could - behaviours and mannerisms associated with the figures I had assigned them, at random, to recreate. Some of the parts I doled out to my guests to play represented certain types of people that could be found in British India throughout both Company and Raj rule - such as the young, upper-class bachelors who ran the Imperial Civil Service, whose view of Indians was one of inherent inferiority, that they were children, incapable of ruling themselves, plucked straight from Britain’s elite public schools and chosen for service often on merit of their family name, or their proximity to the Ideal of the English Gentleman in personality; and members of the Fishing Fleet, a term for unmarried women who fled to India in search of a Civil Service gentleman to wed, who were commonly even more contemptuous towards India and its people than the men whom they were there to pursue. Others, I asked to fashion themselves as actual, named historical figures associated with British rule over the Subcontinent: including Robert ‘Clive of India’ (who pillaged millions of pounds worth of diamonds from the lands and treasuries of Indian territories he subjugated, and used them to buy influence in Parliament and, later, a Peerage); Warren Hastings (who was infamously impeached by Parliament for presiding over a rapaciously corrupt British East India Company, described at the time as not fit to run its own affairs, let alone those of a Continent); and Lord Nathaniel Curzon (a twentieth-century Viceroy of India with a penchant for ornamentalism and extreme delusions of grandeur, who amongst other things poured enormous amounts of money into hosting the lavish Delhi Durbar of 1911 just two short years after a major famine had struck the country). Others still, I asked to pretend to be embroiled in a court case: one figure would pretend, in turn, to be an Indian murdered by a Briton, then a Briton murdered by an Englishman, and another would pretend to be each of the accused murderers; in turn, a final figure, fashioned as a judge in the British Indian legal system, would pass down the sentences the guilty murderer would likely receive in these two cases, calling attention to the unimaginably severe differences between the way the colonial legal system treated native Indians and their British colonisers.

Pictured here, after the tablecloths, candelabras and silverware adorning the dining table the East India Club had prepared for us were removed and stored away, out of sight, Joan is scribbling the objective truth - ‘The East India Club is Racist, Sexist and Classist’ - on a sheet of paper laid the length of the table with the help of guest Hannah Job. Photo courtesy Michelle Williams Gamaker.

Joan Carpenter, flippantly handing her adorable little baby, to Purse the Nurse (Lucia Coppola) in her Creche - overseen, in the background, by the glancing eyes of a portrait of the final King of Oudh, deposed by the British during the 1857 Rebellion. Photo courtesy Michelle Williams Gamaker.

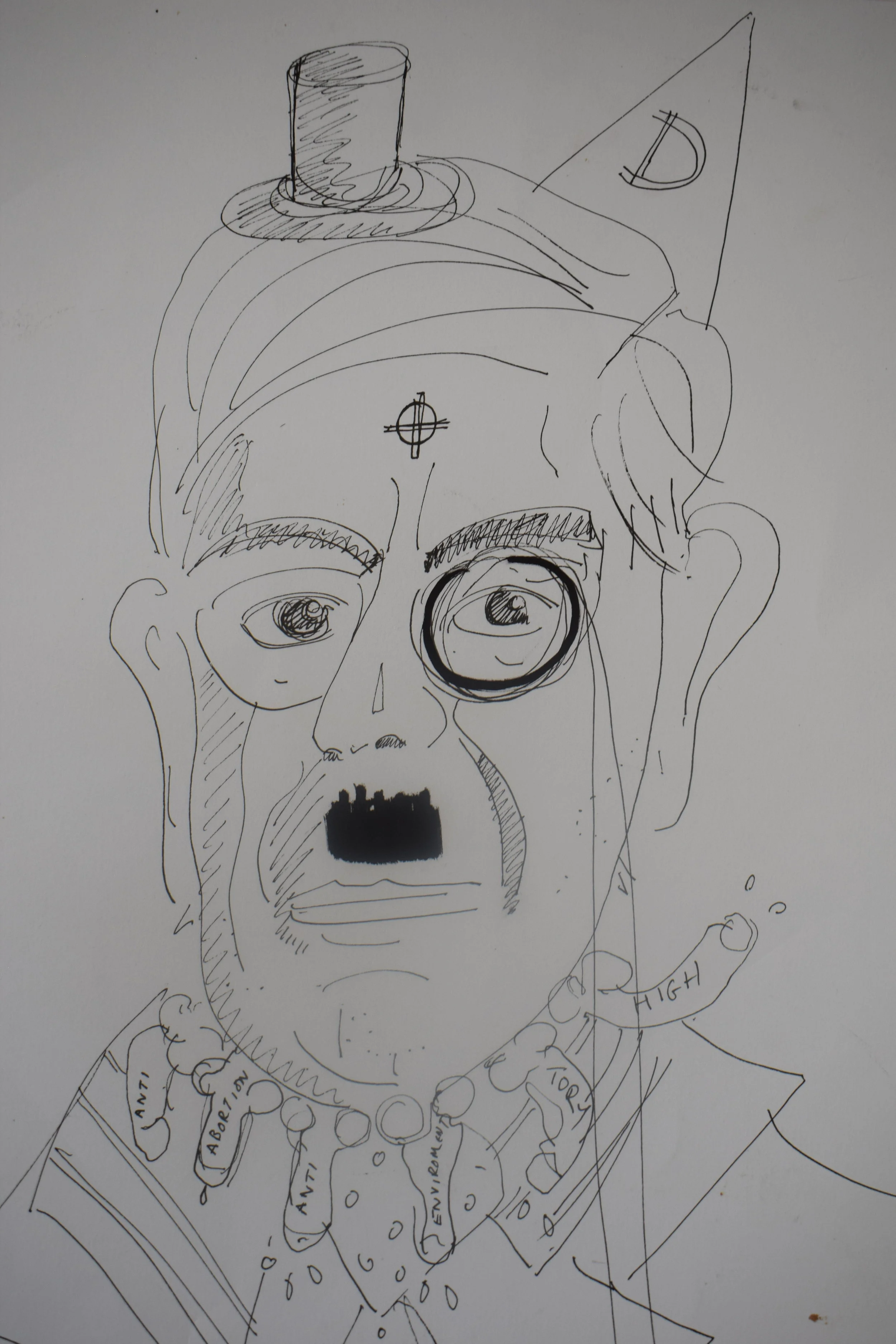

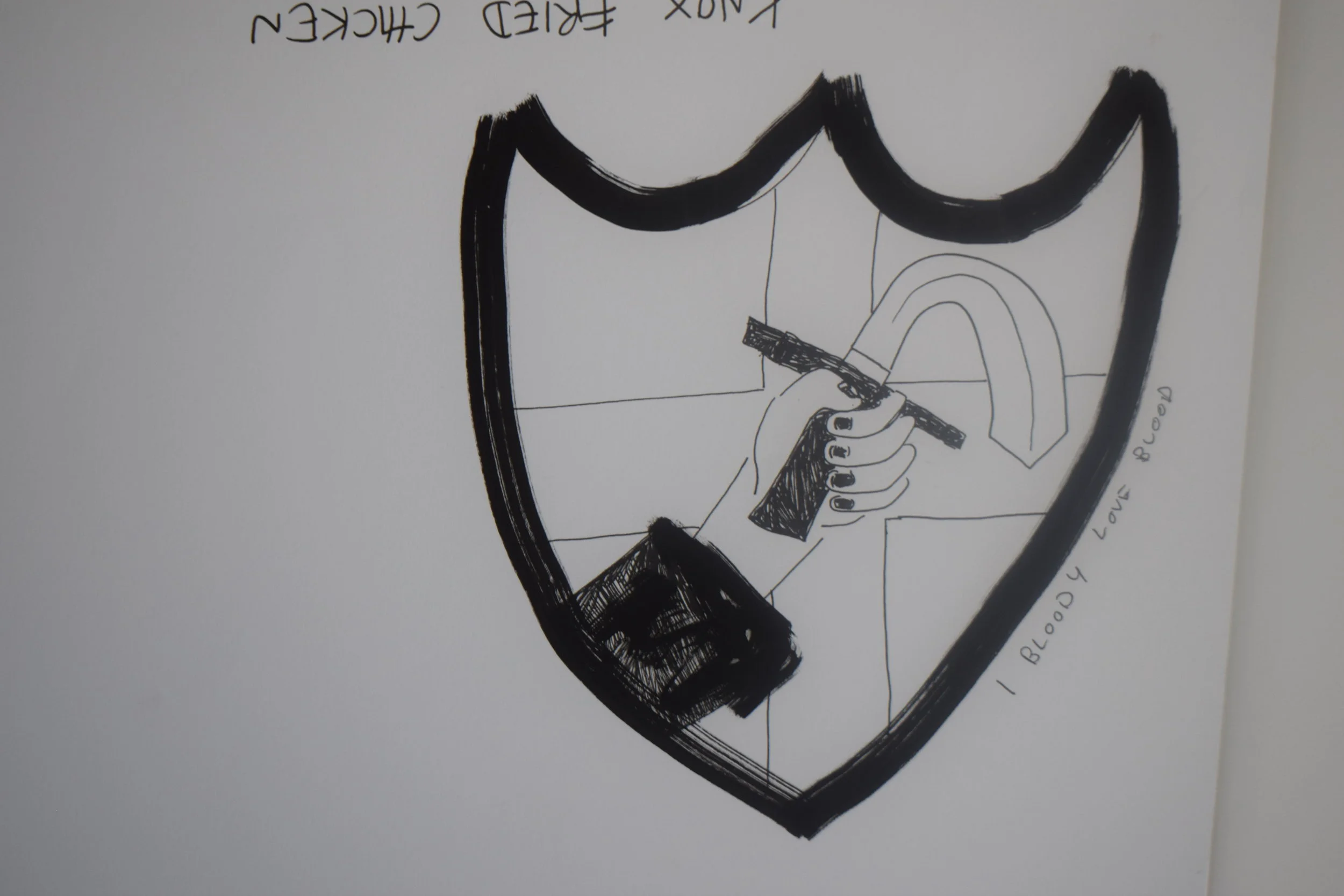

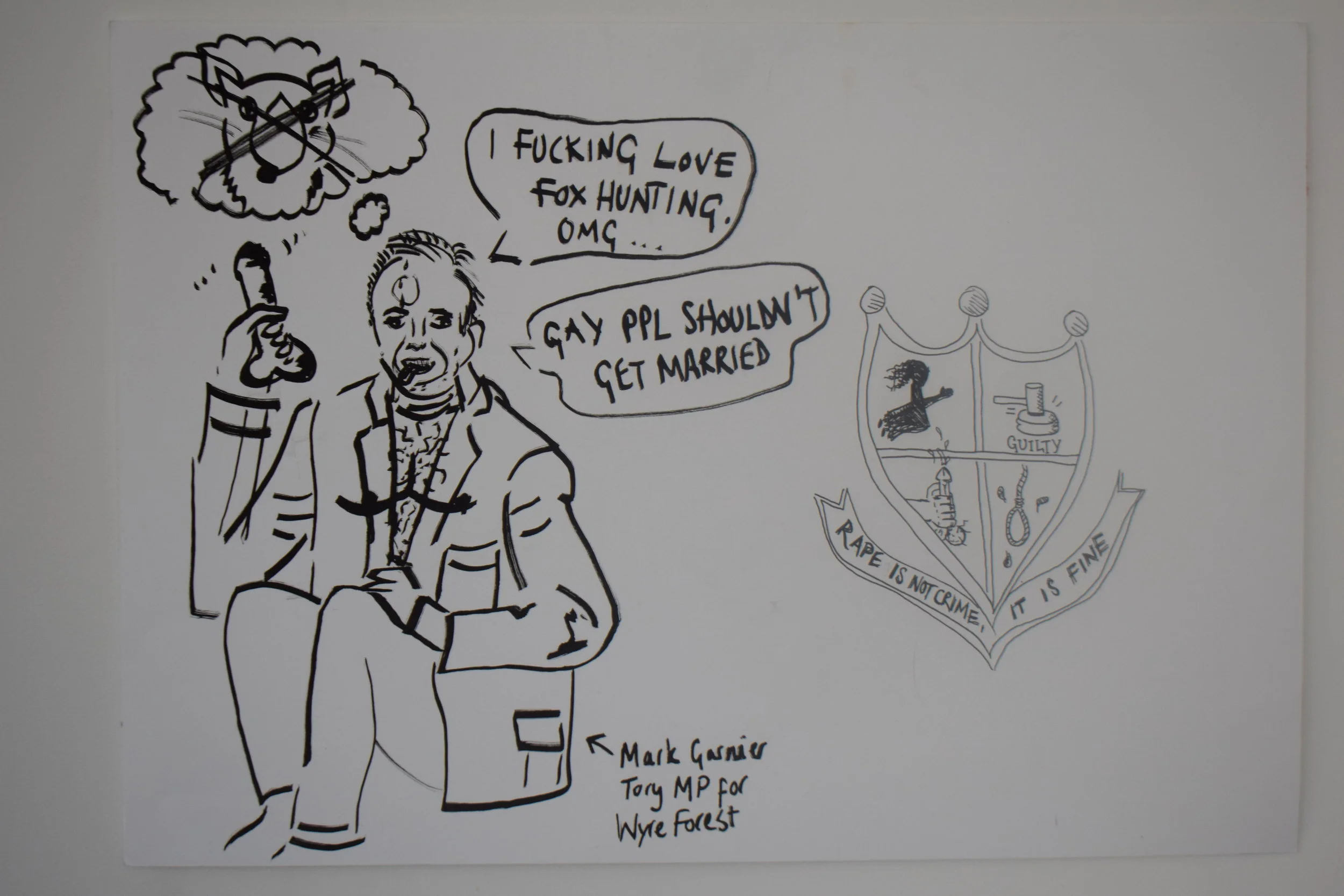

The night’s final activity - named Joanie’s List of Wanton Westminster Wankers - involved us taking a few pot-shots at some deserving political figures, through the medium of satirical caricature. Prior to arriving, I asked all of my guests to bring a photograph of a noteworthy political or social figure whom had caused harm to them directly through their policies or rhetoric, or to others they knew, loved, or had closely befriended - with the strict instruction that said figure could not be too obvious a choice, meaning the likes of Theresa May, Boris Johnson, Nigel Farage and Donald Trump were off-limits - to transform into a caricature inspired by Harris’ List of Covent Garden Ladies: a Regency-era directory documenting West End prostitutes and the properties from which they did their business, accompanied with illustrations and erotic descriptions written by, and tailored for, the racist, sexist, classist straight British gentleman’s gaze. A collection of the drawings that were produced - under unfortunately strict time constraints, due to problems with the Tube that evening meaning the whole event started almost half an hour later than billed - can be seen in the slideshow at the bottom of the page.

Although most of us had already long since stripped out of the formal wear East India Club regulations demanded we wear to gain access to it - myself, personally, halfway through my opening address - whilst packing up our props, rolling up the paper scroll we had draped across the table, and tidying the whole room so it would be left cleaner than it had ever been left by a private booking’s attendees before, out of respect for the Club’s staff of waiters and housekeepers, all guests who had not already done so removed their dresses, suits and smart separates, in order to parade from the building as our legitimate selves, freed from the classist trappings such institutions insist upon demanding their members and guests adorn. At quarter past eleven that Friday night, we stole a few final group photographs on the Club’s front steps, in an eerily silent Saint James’s Square, and then Joan Carpenter and her Esteemed Guests went their separate ways.

My thanks, once again, must go out to all whom attended.